Hundreds of day hikes, rock climbing routes and mountain peaks over many years never caused me more than bruises and scratches. But last October, I slipped on a patch of ice on an easy trail and caused “massive” damage to my rotator cuff. I knew rotator cuffs allowed shoulders to do all they do, and that baseball pitchers, understandably, are susceptible to rotator cuff tears. I had no idea how easily and forcefully a tear can be life changing. It turns out rotator cuff injuries are common, can be caused by normal wear and tear as well as trauma, and range from minor and self-healing, to massive where recovery requires surgery. I wish I’d been more aware of rotator cuff vulnerabilities and had taken more precautions (paying better attention to the terrain, using better hiking boots, walking sticks, etc). Maybe my story will help prevent an injury. If you’re looking for work and perhaps in some financial stress, a nasty rotator cuff injury can make those things far far worse.

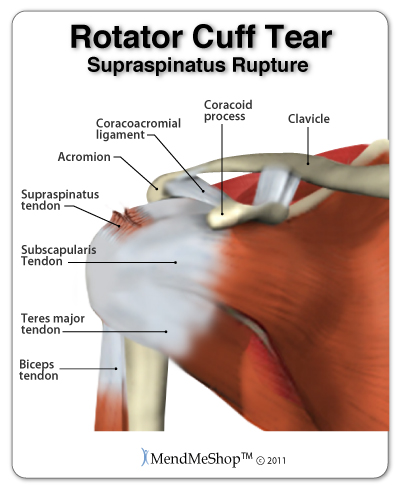

Briefly, a rotator cuff is a set of four muscles and associated tendons that wrap around the arm bone (humerus) and connect it to the shoulder blade (scapula). Rotator cuffs give our shoulders their amazing strength and dexterity. This image is from here.

I slipped and hit the ground hard. 15 minutes later I figured nothing was broken or dislocated. Whew! I went in to urgent care a couple of days later to make sure, got an X-ray and was told by the doc that everything was fine. It wasn’t*, but I didn’t realize that until a week later when it hurt less and the swelling had gone down, but I couldn’t raise my arm. I got an appointment with the sports medicine doc two weeks after the injury. His nurse checked me out for 2 minutes and said she thought it was a rotator cuff tear. The doc agreed, and ordered an MRI. The radiologist who did the initial MRI read said one “full tear” another probable full tear, and some other partial tears.

The muscle-tendon combination connecting bone to bone is under tension and when it suffers a full tear, the split ends retract like rubber bands, and can’t heal back together. Surgery is required to reattach the torn ends back together. So we set a date – mid-December, two months after the injury.

This was my first surgery, so I can’t personally compare it to the old days, but it was amazing: outpatient arthroscopic surgery (no big incisions), bandages off and OK to shower just 36 hours after the surgery. In addition to the general anesthetic for the operation, I got a “nerve block” that prevents all feeling in the shoulder and arm for about 24 hours. I was out of course during the operation but the before and after were downright pleasant.

Except for the news. Three full tears plus one nearly full tear. These are big tendons and they take a long time to heal. Six weeks of immobilization in a special sling, then six weeks of physical therapy to restore mobility (evidently shoulders like to freeze up when they get a chance) but where I must not use the affected muscles. Then six more weeks of beginning to use the muscles but with no external weights. Then six more where I actually begin strength training with tiny weights. Twenty-four weeks after the surgery (almost 8 months after the injury), I’ll still be far from full recovery, but should be back to a reasonable ability to handle life’s basic tasks. IF, that is (it’s a big if) the surgery holds.

The reason I must not exercise the repaired muscles prematurely is that I can tear the suture(s) apart. How likely this is, is hard to pin down because it depends not only on my attempts to stay limp, but on the quality of the tissue (is it a clean tear or is the tissue frayed, patient age, is there scar tissue from prior non-traumatic injuries in the area). Trying not to flex the muscles is subject to reactive movements, bumps or falls, even dreams. I won’t know if the surgery was successful until well into my third 6-week phase of physical therapy, because initially I can’t test those muscles, and later on, they’ll be so weak from months-long dis-use and atrophy that it’ll be hard to tell if they’re attached or not.

Physical therapy is painful as I work to regain mobility. More importantly, it’s intimidating as I try to differentiate between movements that are OK and “just” painful versus those that can cause damage to the sutures. At this point, I’ll know in 2 to 3 months if the surgery will wind up leading to good recovery. The best guess I have is around 15% of surgeries similar to mine fail. Good odds, but not great.

My physical therapy is 2 hours per week, plus the home exercises, which I’m to do basically as often as possible. My physical therapist said this will be my most inconvenient year. But the therapy and exercises aren’t bad. By far the larger inconvenience is that I have only one good arm. No more fixing whatever goes wrong around the house, almost everything takes far longer from making a sandwich to buckling a belt to brushing teeth (my dominant arm is the damaged one). Happily I can use the fingers of my bad arm to type, somewhat. I got a split keyboard “Kinesis Freestyle2” which lets me go about half of normal speed.

Imagine cutting your to-do list by 80%. Injuries like this are exceedingly forceful in prioritizing what can actually get done. For me, it also delivered a big dose of empathy for others who are disabled. For these things, I’m very grateful. My disability is at least (probably) temporary; for so many others, whether by injury or birth or war or disease, it’s permanent. Last year I read a book about John Wesley Powell, who famously was the first to navigate the Colorado River. He’d lost an arm in the civil war which continued to cause him pain for the rest of his life, but that didn’t stop him from returning to the army to fight more battles, from becoming a professor of Geology, of leading exploratory expeditions into the Rocky Mountains, of becoming Director of the US Geological Survey where he initiated the topographical mapping of the US, of being one of the prime advocates of land conservation and a scientific approach to irrigating the vast tracts of new land just being explored. His would have been an incredible life if he’d had two arms. How in the world did he manage it all with one? Amazing and humbling.

May you never have to go through such an injury and long recovery. But if you do, it does open up a new world of perception – that a lot of disabled yet resilient people live far more difficult lives than the rest of us understand.

* It’s an interesting question whether urgent care should have done more. There was no emergency treatment needed, but they could have done the 2 minutes of simple testing to diagnose a common problem, or recommended I follow up with a specialist. I don’t fault them, but it could be a lot better.